By Adv. M. N. Khan, Chandrapur

Introduction: Transparency Meets Procedural Discipline

The Right to Information Act, 2005 is widely regarded as one of India’s most powerful democratic legislations. It empowers citizens to demand accountability from public authorities and strengthens participatory governance. However, as the law matures, courts and commissions continue to define its boundaries.

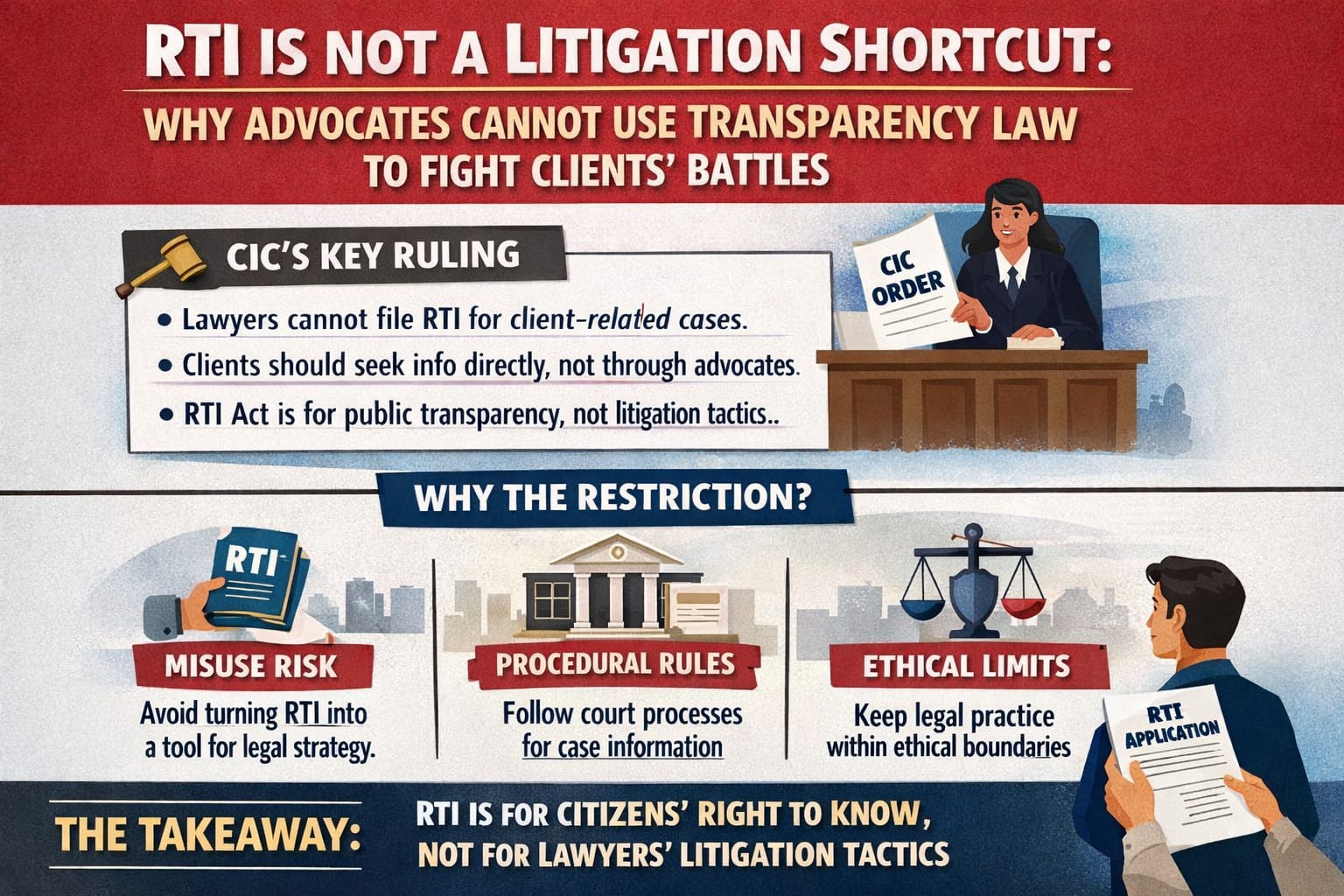

A recent decision of the Central Information Commission (CIC), holding that advocates cannot invoke the RTI Act on behalf of their clients in relation to pending or connected litigation, has triggered intense discussion within legal circles.

“Can a lawyer, acting as a legal representative, use the RTI Act as a tool to gather information for a client’s case?”

The CIC has answered this in the negative — and in doing so, has reshaped an important aspect of legal practice.

The Core Issue Before the Commission

The case before the CIC involved an advocate who filed an RTI application seeking information from a public authority concerning a contractual dispute. The application was expressly stated to be on behalf of the client. When the information was denied, the matter reached the Commission in second appeal.

The Commission rejected the appeal and laid down a clear principle:

“The RTI Act cannot be converted into a mechanism for conducting litigation or advancing professional legal practice.”

Citizenship Versus Professional Capacity

The Commission acknowledged that an advocate is undoubtedly a citizen. However, it emphasised that the capacity in which the information is sought is crucial.

When an RTI application is filed purely to advance a client’s litigation, the character of the RTI request changes.

The CIC observed:

“The client himself is competent to seek information under the RTI Act. The advocate cannot act as a proxy to invoke the Act for litigation purposes.”

RTI Is Not a Parallel Litigation Tool

The Commission cautioned that allowing advocates to routinely file RTI applications for their clients would create a parallel system of discovery outside courts.

“RTI cannot be permitted to bypass established judicial procedures of evidence, discovery, and inspection.”

Courts already provide mechanisms such as discovery, interrogatories, summons, and judicial directions. RTI cannot replace these processes.

Judicial Support for the CIC View

The Commission relied on High Court precedents which consistently hold that RTI should not be used to obtain information relating to matters sub judice in order to gain litigation advantage.

“RTI is a transparency law, not a litigation strategy.”

Doctrinal Justification

Litigation is governed by special procedural statutes such as the Code of Civil Procedure, Code of Criminal Procedure, and tribunal rules. These special laws override general mechanisms like RTI when the subject matter is litigation-related.

Administrative and Institutional Concerns

If advocates are allowed to use RTI as a litigation tool, public authorities would face tactical filings, administrative burdens, and delays for genuine transparency seekers.

Addressing the Criticism

The ruling does not curtail the client’s right. The client remains free to file an RTI application personally. What is restricted is only the professional proxy use.

“The right under RTI is a democratic entitlement of the citizen, not a transferable professional instrument.”

RTI Is Not a Law of Agency

The RTI Act does not function on principles of agency. It is not designed to operate like a power of attorney. The right is personal to the citizen.

Ethical Dimensions

Using RTI to secure information that would otherwise require judicial permission raises ethical concerns and may prejudice the opposing party.

Protection of Sub Judice Proceedings

RTI authorities are not equipped to balance disclosure with trial fairness. Courts alone possess the institutional competence to decide what should be disclosed during litigation.

Not a Blanket Ban on Advocates

An advocate may still file RTI applications in personal capacity or in public interest. The restriction applies only when the RTI is connected to a client’s case.

Guidance for Litigants

RTI is not a substitute for procedural remedies in court. Discovery applications, summons, and judicial directions remain the appropriate routes.

Lessons for Young Advocates

“The strength of advocacy lies not in shortcuts, but in mastery of lawful procedure.”

Preserving the Democratic Character of RTI

If RTI were perceived as a litigation weapon for lawyers, its legitimacy as a citizen’s transparency tool would suffer.

Conclusion

The CIC’s ruling protects the citizen-centric character of RTI, upholds procedural integrity in litigation, and reinforces ethical advocacy.

“The rule of law thrives not on exploitation of loopholes, but on respect for institutional balance.”

The RTI Act remains a powerful instrument of transparency. Its effectiveness depends on responsible use by citizens and principled restraint by professionals.

Disclaimer

The present article and accompanying infographic are intended solely for academic, informational, and public awareness purposes. They do not constitute legal advice, legal opinion, or professional solicitation. The views expressed herein are personal to the author, based on a reading of the Right to Information Act, 2005, and reported decisions of the Central Information Commission and courts as available in the public domain. Readers are advised to independently verify the law and consult a qualified legal professional before relying upon or acting on the contents of this publication.

By Adv. M. N. Khan, Chandrapur

Introduction: Transparency Meets Procedural Discipline

The Right to Information Act, 2005 is widely regarded as one of India’s most powerful democratic legislations. It empowers citizens to demand accountability from public authorities and strengthens participatory governance. However, as the law matures, courts and commissions continue to define its boundaries.

A recent decision of the Central Information Commission (CIC), holding that advocates cannot invoke the RTI Act on behalf of their clients in relation to pending or connected litigation, has triggered intense discussion within legal circles.

“Can a lawyer, acting as a legal representative, use the RTI Act as a tool to gather information for a client’s case?”

The CIC has answered this in the negative — and in doing so, has reshaped an important aspect of legal practice.

The Core Issue Before the Commission

The case before the CIC involved an advocate who filed an RTI application seeking information from a public authority concerning a contractual dispute. The application was expressly stated to be on behalf of the client. When the information was denied, the matter reached the Commission in second appeal.

The Commission rejected the appeal and laid down a clear principle:

“The RTI Act cannot be converted into a mechanism for conducting litigation or advancing professional legal practice.”

Citizenship Versus Professional Capacity

The Commission acknowledged that an advocate is undoubtedly a citizen. However, it emphasised that the capacity in which the information is sought is crucial.

When an RTI application is filed purely to advance a client’s litigation, the character of the RTI request changes.

The CIC observed:

“The client himself is competent to seek information under the RTI Act. The advocate cannot act as a proxy to invoke the Act for litigation purposes.”

RTI Is Not a Parallel Litigation Tool

The Commission cautioned that allowing advocates to routinely file RTI applications for their clients would create a parallel system of discovery outside courts.

“RTI cannot be permitted to bypass established judicial procedures of evidence, discovery, and inspection.”

Courts already provide mechanisms such as discovery, interrogatories, summons, and judicial directions. RTI cannot replace these processes.

Judicial Support for the CIC View

The Commission relied on High Court precedents which consistently hold that RTI should not be used to obtain information relating to matters sub judice in order to gain litigation advantage.

“RTI is a transparency law, not a litigation strategy.”

Doctrinal Justification

Litigation is governed by special procedural statutes such as the Code of Civil Procedure, Code of Criminal Procedure, and tribunal rules. These special laws override general mechanisms like RTI when the subject matter is litigation-related.

Administrative and Institutional Concerns

If advocates are allowed to use RTI as a litigation tool, public authorities would face tactical filings, administrative burdens, and delays for genuine transparency seekers.

Addressing the Criticism

The ruling does not curtail the client’s right. The client remains free to file an RTI application personally. What is restricted is only the professional proxy use.

“The right under RTI is a democratic entitlement of the citizen, not a transferable professional instrument.”

RTI Is Not a Law of Agency

The RTI Act does not function on principles of agency. It is not designed to operate like a power of attorney. The right is personal to the citizen.

Ethical Dimensions

Using RTI to secure information that would otherwise require judicial permission raises ethical concerns and may prejudice the opposing party.

Protection of Sub Judice Proceedings

RTI authorities are not equipped to balance disclosure with trial fairness. Courts alone possess the institutional competence to decide what should be disclosed during litigation.

Not a Blanket Ban on Advocates

An advocate may still file RTI applications in personal capacity or in public interest. The restriction applies only when the RTI is connected to a client’s case.

Guidance for Litigants

RTI is not a substitute for procedural remedies in court. Discovery applications, summons, and judicial directions remain the appropriate routes.

Lessons for Young Advocates

“The strength of advocacy lies not in shortcuts, but in mastery of lawful procedure.”

Preserving the Democratic Character of RTI

If RTI were perceived as a litigation weapon for lawyers, its legitimacy as a citizen’s transparency tool would suffer.

Conclusion

The CIC’s ruling protects the citizen-centric character of RTI, upholds procedural integrity in litigation, and reinforces ethical advocacy.

“The rule of law thrives not on exploitation of loopholes, but on respect for institutional balance.”

The RTI Act remains a powerful instrument of transparency. Its effectiveness depends on responsible use by citizens and principled restraint by professionals.

Disclaimer

The present article and accompanying infographic are intended solely for academic, informational, and public awareness purposes. They do not constitute legal advice, legal opinion, or professional solicitation. The views expressed herein are personal to the author, based on a reading of the Right to Information Act, 2005, and reported decisions of the Central Information Commission and courts as available in the public domain. Readers are advised to independently verify the law and consult a qualified legal professional before relying upon or acting on the contents of this publication.