Trusted Legal Guidance

At Adv. Nazim Khan Legal Chambers, we offer trusted expertise in criminal, civil, and family law.Our criminal law practice ensures strong defense and protection of your rights.

In civil matters, we provide clear strategies for resolving disputes effectively.With family law, we guide you through sensitive issues with care and professionalism.We are committed to delivering reliable legal solutions with integrity at every step.

Our Services

Dedicated to delivering justice, fairness, and peace of mind in every case.

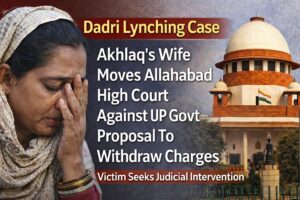

Criminal Law

With proven expertise in criminal law, we handle complex cases with precision. From defense to appeals, we safeguard your freedom at every step.

Family Law

Our family law services cover divorce, custody, maintenance, adoption, and domestic disputes with legal solutions that prioritize fairness, dignity, and peace of mind.

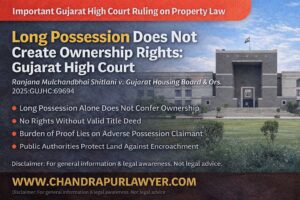

Property Law

Our property law services cover registration, documentation, and litigation. We provide clear guidance to ensure your property matters are handled with confidence.

Consumer Rights

Our consumer rights services address complaints, disputes, and grievances. We stand by you to ensure honesty, fairness, and accountability in every case.

Dedicated Team of Attorneys

Chris Smith

Civil Rights Law

Jada Dawson

Commercial Law

William Gibbs

Corporate Law

Rosa Parks

Criminal Law

Are you A law graduate? apply for an internship with us

Step into the world of practical law with our internship opportunities. Gain skills, mentorship, and confidence for your future.

Let's win your case

We believe every case deserves dedicated attention and a winning strategy. With our proven legal expertise, we fight for your rights and deliver results you can trust.

Why Choose Our Legal Services

We combine experience, strategy, and dedication to secure the best outcomes.

Experienced Legal Professionals

Our skilled lawyers bring years of expertise across criminal, family, property, and consumer law, ensuring you receive strong representation.

Best Case Strategies

We analyze every detail to craft the strongest legal strategy, tailored to your unique situation for the best possible outcome.

With You - From Start to Finish

From your first consultation to the final resolution, we stand by your side, guiding you with transparency, care, and commitment.

Testimonials

Real stories of trust, justice, and successful outcomes.

Request a Free Consultation

Take the first step toward justice with a confidential consultation.