A LiveLaw-Style Analysis of Madarsa Ahle Sunnat Imam Ahmad Raza v. State of Uttar Pradesh, Writ-C No. 307 of 2026

Introduction: When Regulation Becomes Suppression

Can the State shut down an educational institution merely because it lacks formal recognition, even when the law prescribes no such consequence?

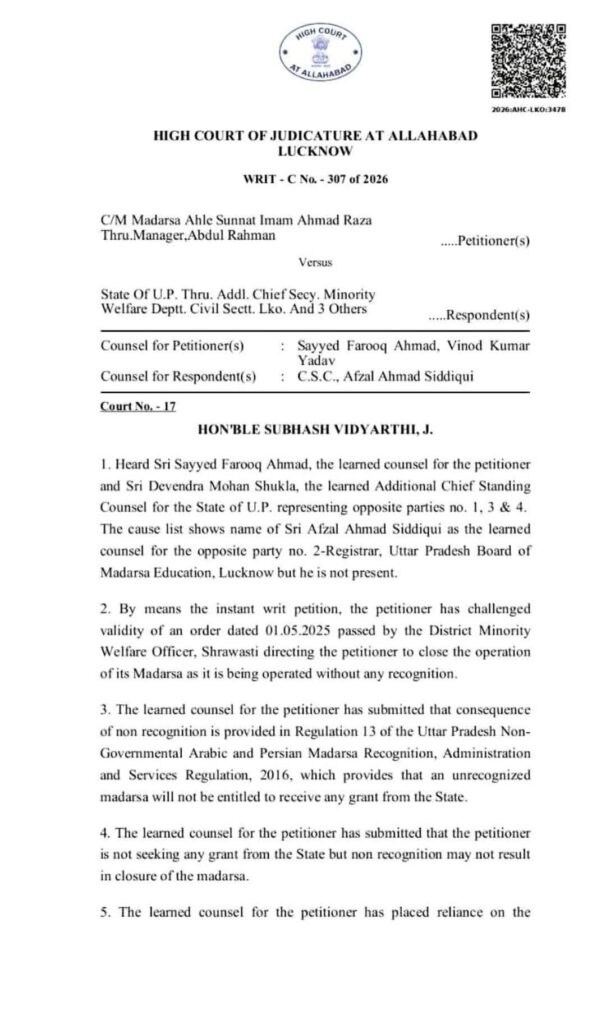

This constitutional question lay at the heart of Writ-C No. 307 of 2026, decided by the High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, Lucknow Bench. The Court decisively held that non-recognition of a Madarsa does not, by itself, justify its closure.

In an era where regulatory oversight of minority institutions increasingly intersects with constitutional freedoms, the judgment delivered by Hon’ble Justice Subhash Vidyarthi assumes particular significance. It reasserts a foundational principle of administrative law.

“What the statute does not expressly permit, the executive cannot enforce by implication.”

Factual Matrix: Closure Order Triggered by Non-Recognition

The petitioner, C/M Madarsa Ahle Sunnat Imam Ahmad Raza, through its Manager Abdul Rahman, challenged an order dated 01 May 2025 passed by the District Minority Welfare Officer, Shrawasti.

The impugned order directed the Madarsa to close its operations solely on the ground that it was functioning without recognition under the Uttar Pradesh Madarsa regulatory framework.

The Madarsa did not dispute its unrecognised status. Instead, it raised a fundamental legal question:

Does lack of recognition empower the State to order closure of an educational institution?

Arguments Before the Court

Petitioner’s Submissions

The petitioner relied upon Regulation 13 of the Uttar Pradesh Non-Governmental Arabic and Persian Madarsa Recognition, Administration and Services Regulation, 2016, contending that:

- The only consequence of non-recognition is denial of grant-in-aid.

- The Regulations do not provide for closure.

- The Madarsa was not seeking any financial assistance.

- The closure order was ultra vires and illegal.

State’s Stand

The State defended the action by arguing that recognition is essential for lawful functioning. However, no statutory provision authorising closure was cited.

Judicial Reasoning: Regulation Cannot Travel Beyond the Statute

The Court observed that:

- The Regulations distinguish recognition from entitlement to benefits.

- Regulation 13 only denies grant-in-aid.

- No authority exists to shut down an unrecognised Madarsa.

“Executive authorities cannot impose consequences that the statute itself does not prescribe.”

Accordingly, the closure order was held illegal.

The Constitutional Undercurrent: Article 30

Madarsas enjoy protection under Article 30(1) of the Constitution. Regulation must be reasonable and must not destroy the core right of minorities to administer their institutions.

A closure order without statutory authority would violate this constitutional protection.

Regulation vs Prohibition

The Court reaffirmed that recognition regulates privileges, whereas closure amounts to prohibition, which requires legislative sanction.

Why This Judgment Matters

This ruling affects:

- Private unaided schools

- Minority colleges

- Vocational and religious institutions

Non-recognition alone cannot be used as a weapon to shut down institutions.

Administrative Overreach Checked

The judgment reminds authorities that administrative convenience cannot override statutory limits. Regulation must remain within legal boundaries.

Final Outcome

- Closure order dated 01.05.2025 was quashed.

- The Madarsa was allowed to continue functioning.

- Non-recognition was held to affect only grant entitlement.

Conclusion: Rule of Law Over Regulatory Anxiety

“Non-recognition is not a death warrant.”

Unless the legislature clearly mandates closure, administrative authorities cannot invent penalties by executive action.

This judgment restores constitutional balance, statutory discipline, and the supremacy of the rule of law.

Editorial Note – ChandrapurLawyer.com

This decision is likely to be cited in future challenges against arbitrary closure orders across India. Legal practitioners dealing with education law, minority rights, and administrative law should closely follow its application.